Tuesday, July 31, 2007

All-Stars Not All Good

Vick is accused of being involved in a dogfighting scheme. One of his associates has already pleaded guilty and indicated he will provide evidence that could prove detrimental to Vick, both legally and professionally since the NFL's new commissioner Roger Goodell is determined to rid the NFL of criminal activity after years of legal woes. Goodell has already banned Vick from training camp for the indictment alone (nevermind that if Vick is found not-guilty he could sue the league).

Bonds is accused of using steroids to expedite (if not make possible altogether) his rise to baseball's greatest home run hitter ever. Ahead of fellow African-American sports great Hank Aaron who received death threats throughout 1973 and '74 while he was approaching Babe Ruth's record of 713 home runs. It's also important to note that Bonds, too, has a friend who has already been positively linked to his accusation; thankfully for Bonds, his friend has remained tight-lipped in prison (and most believe will remain so for a friendly payoff upon his release).

Regardless of what the reasons for Vick's alleged dogfighting "hobby" and Bonds' alleged steroid use (and perjury under a federal grand jury), it's unfortunate that these men are now more known for their legal troubles than their contributions to their respective teams' success.

I don't have the information necessary to predict the outcomes of each sports figure's legal circumstances, but I can say with all certainty that these stars have already begun the downward spiral from the galaxy's mountaintop they were once lifted into for nothing more than athletic prowess.

Too often, we elevate sports figures and other celebrities to role model status without justification outside of their talent on the hardwood or Astroturf. It's troubling that we can't give the same prestige to doctors, engineers, police officers, and other professionals who use their talents and abilities to improve their lives and the lives of others.

That said, I'm not surprised when a star athlete is negatively influenced by hanger-on friends that don't have his best interest in mind? And I don't act surprised when a sports star finds a way to work around the system to improve his chances for success on the field?

Instead, I think Vick and Bonds are prime examples of why it's so important to recognize the real role models in the African-American community. The people that earn the "role model" designation because of their hard work and commitment to a profession without expecting signing bonuses, MVP awards, and endorsement deals.

There are plenty of examples of real role models in professional sports, but part of me thinks the jury has already found Vick and Bonds guilty of false impersonation.

Monday, July 30, 2007

Helping Build a Business and Save Lives

"I hope all is well. I am sending you this message because I dont have many friends and allies, and I need all 16 of them--including you--to help me with something big.

--

Christien D. Oliver

H2bid.com, Executive Vice President

-Providing access to water and wastewater contract opportunities from around the world."

Sunday, July 29, 2007

More Good Info from Don Cheadle

| Kemp Powers |

| Reuters |

Thursday, July 26, 2007

|

LOS ANGELES (Reuters) - Don Cheadle has become known as one of Hollywood's more socially active stars since his Oscar-nominated role in 2004's "Hotel Rwanda."

His new film, "Talk to Me," about a 1960s radio disc jockey and social activist, debuted in major U.S. cities on July 13 and expands nationwide in coming weeks.

Cheadle, 42, spoke to Reuters about being an African American actor in Hollywood and using his stardom to promote social causes:

Q: Along with stars like George Clooney, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, you're viewed as one of the more socially active actors in Hollywood. What drives you to be involved in social and charitable endeavors?

A: "I think I was pulled into the stream of activism after "Hotel Rwanda." We filmed the movie in South Africa, and a lot of the South African actors said they didn't know what was happening in Rwanda, which for all intents and purposes was up the street from them. And then Darfur (in Sudan) happened, and people found out about it, but still nothing was happening."

Q: So how did you end up involved?

A: "I went on a trip with several congressmen and women, Democrat and Republican, and saw with my own eyes what had happened. Talking with people, breaking bread with them, laughing and playing with their kids. Those manufactured walls between who we are melted away really fast. One of the few worthy ancillary benefits of fame and celebrity is to take the focus, when it's put on you, and throw it onto other things."

Q: It seems there are only a few African American actors who can get a film made including you. Is that accurate?

A: "There's probably 10 actors of any ethnicity who can really write their own ticket. And probably 8 of the 10 don't really feel that way about themselves. So I don't feel like I've made it but I know that I can get a movie greenlit at a certain budget."

Q: Do you feel that black actors of your stature have any kind of artistic obligation to do certain types of films?

A: "No. I would never presume to tell someone else what they need to be doing. It would be great to do a role where you got $19 million, or however many million dollars you need to help you coast through life. But in order to take care of all the things I need to take care of ... I'd have to make four or five movies a year, which starts to show diminishing returns. You're doing all of this for (your family), but you never get to see them because you're never there. I think a lot of that went into my decision to produce, because the five stages of an actor's career are real."

Q: What are those five stages?

A: "Who is Don Cheadle? Get me Don Cheadle. Get me a Don Cheadle type. Get me a young Don Cheadle. Who is Don Cheadle? By the time it gets back to the second "who is Don Cheadle?" I want to know enough about this business that I can continue to be a creative and hopefully productive, lucrative part of this business."

Q: With international box office becoming an increasing part of the Hollywood financial equation, are you worried that it will negatively affect black actors who, some say, cannot be relied upon to draw people to box offices overseas?

A: I don't necessarily believe that black films and black actors don't travel. There's sometimes a lack of (marketing) on those films. It can be a self-fulfilling prophecy if you don't spend 'Spidey' money on a movie like "Talk to Me" and then say "oh, it doesn't work." When I do international press, people approach me all the time and say "we love you in Europe, in Asia, in South America," and so on. There's definitely an audience there."

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Hip-Hop History

That said, I've written a lengthy, if not comprehensive, history of hip hop. Regardless of your liking or disliking of current rap music, this is a must-read if you don't know who DJ Kool Herc, Big Daddy Kane or Lupe Fiasco are.

A Hip-Hop History Lesson

DJ Kool Herc is considered the “pioneer of hip hop” because he brought the dancehall influences of his Jamaican childhood to Bronx, New York in the mid-1970s. As early as 1973, Herc would throw parking lot parties playing music with huge speakers in the backseat of his car. Eventually others caught on and by the late ‘70s and turn of the decade, Grandmaster Flash and The Sugarhill Gang, of “Rapper’s Delight” fame were notable hip hop artists in New York.

Based on the success of “Rapper’s Delight” and following Blondie’s “Rapture” and Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust”, hip hop was starting to catch mainstream attention. By this point in the early 1980s, hip hop was well established in New York and had expanded to the streets of Los Angeles. Break dancing, rapping, graffiti (and to a lesser degree beatboxing) were the major tenets of the hip hop culture at this time. Fashion followed suit with jumpsuits, Kangol hats, Shell top adidas, and other trends that have influenced fashion for years since.

Just around the time MTV and BET were working out their early-year kinks, hip hop was getting ready for primetime and a young entrepreneur and his Jewish friend were ready to capitalize on the opportunity. With the creation of Def Jam Records by Russell Simmons and producer Rick Rubin, Run-DMC quickly rose to pop fame. The group consisting of Joseph “Run” Simmons who was Russell’s younger brother, his best friend Darryl “DMC” McDaniels, and later the addition of DJ Jason Mizell, a.k.a. Jam Master Jay), released three albums from 1984 to 1986, including the smash hit album ‘Raisin’ Hell’ which featured the hit single and remix of Aerosmith’s “Walk this Way”. The album sold over 3 million copies and cemented hip hop’s place in popular music.

Further bolstering Def Jam’s success were the rise of hip hop’s first white rappers, a group called Beastie Boys. Their 1986 album “License to Ill” went five time platinum after being the first-ever hip hop album to go #1 on the Billboard chart and earned them a touring gig with Madonna before going on their own world tour with tracks like “Fight For Your Right to Party”.

Ladies Love Cool James, or LL Cool J, was another Def Jam artist to usher in hip hop to the mainstream. The young Queens native was Def Jam’s first official signing and he didn’t disappoint. His 1985 album ‘Radio’ launched a career with Def Jam that remains today, 12 albums later (his 13th album, tentatively titled ‘Exit 13’ will be out this winter). His female-geared tracks “I Need Love” and “’Round the Way Girl” weren’t popular amongst the hardcore rap fans who expected songs like “I’m Bad” and “Mama Said Knock You Out”, but rapping to the women has always been LL’s bread and butter.

By this time, another young rapper from Philadelphia called the Fresh Prince was bringing a pop feel to hip hop. Will Smith, who turned down the opportunity to attend M.I.T., and his DJ friend “Jazzy Jeff” Townes rose to fame on the pop strength of songs like “Girls Ain’t Nothin’ But Trouble” and “Parents Just Don’t Understand”, which also earned the duo a Grammy, making Will Smith the first Grammy-winning rap artist.

Grammys, platinum albums, and MTV’s Yo! MTV Raps and BET’s Rap City were popular programs showcase hip hop music. Just when it seemed hip hop was making the full transition into pop phenomenon, a few lyrical masters hit the scene to help make sure hip hop had some artistic stature as well.

KRS-One’s 1987 debut ‘Criminal Minded’ introduced the voice of the rapper commonly known as “the teacher” because of his education-themed songs. His song “South Bronx” was the battle track directed at Queens-natives Marley Marl and MC Shan who led the Juice Crew, which also featured notable rappers Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, and Kool G Rap. Kane would later go on to solo success in 1998 with his debut album ‘Long Live the Kane’ featuring the classic track “Ain’t No Half-Steppin”.

Also in the later ‘80s, Rakim’s ‘Paid in Full’ album with DJ Eric B. received critical acclaim when it was released that same year and many continue to consider Rakim to be the greatest rap lyricist of all time. Also in ’87, Public Enemy - led by politically-charged rapper Chuck D and hypeman Flavor Flav - released ‘Yo! The Bum Rush Show’ to critic’s delight.

However, the emergence of several artistically gifted and critically acclaimed hip hop artists was met with the full emergence of “gangsta rap” with a South Central Los Angeles group called N.W.A., short for Niggaz With Attitude. The combination of Easy-E, Dr. Dre, DJ Yella, MC Ren, D.O.C., Ice Cube, and Arabian Prince and Krazy Dee (both would leave before NWA’s peak) would go on to record ‘Straight Outta Compton’ which went three times platinum and introduced America to street-life and anger like never before.

Counter-balancing the anger-infused songs of groups like NWA were the hip hop party and melodic tracks by New York’s newest hip hop innovators, known as the Native Tongues crew. Led by the 1988 debut success of Long Island-based trio De La Soul (‘3 Feet High and Rising’) and the 1989 follow-up by another trio called A Tribe Called Quest (‘People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm’), hip hop had new voices. Queen Latifah also came out of this hip hop crew and her debut, ‘All Hail the Queen’, was commercially successful as well. The success of these artists coincided with the growing success of Source magazine, started by Harvard students David Mays and Jon Schecter in 1988. Source quickly became the go-to hip hop publication and it’s “5 Mic” designation certified an album as a classic. Many of the aforementioned albums by Run-DMC, LL Cool J, Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, Big Daddy Kane, Eric B. and Rakim, KRS-One, N.W.A. and both De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest earned this designation.

However, with the decline of New York-based rappers like Rakim, Kane, Run-DMC, and KRS-One, NWA jumpstarted the West Coast takeover of rap music. The only concern was that hip hop was left in New York and gangsta rap would become the new norm. By the early ‘90s, Ice Cube had launched a successful solo career, Dr. Dre finagled his way out of his contract with NWA and Easy E to move to Death Row Records and join newly-signed rapper Snoop Doggy Dogg.

With the commercial success of artists like MC Hammer and Vanilla Ice, West Coast rappers felt the need to continue showing America that rap music wasn’t all dance and gimmick. Just around this time, Ice Cube’s solo career was flourishing and rappers like Will Smith were crossing over into TV and film, landing Cube a role in the John Singleton 1991 film ‘Boyz in Da Hood’ which would jumpstart a new era in black cinematography by displaying ghetto life in places like Compton and Long Beach.

The following year, Dr. Dre’s masterpiece ‘Chronic’ hit stores and instantly became a rap classic with songs like “Nuthin’ But a G Thang” and “Let Me Ride” rising up the charts and helping the album sell millions of copies. In 1993, Snoop’s ‘Doggystyle’ nearly matched ‘Chronic’ with its album sales with chart-topping songs like “Gin and Juice”. The East Coast, especially New York, resented the high profile of West Coast rap and envied the millions they were seeing Dr. Dre, Snoop and Ice Cube making on a music form they felt they owned and built.

The East Coast retaliated with a slew of classic, critically if not all commercially successful, albums. From 1993 to 1996, several new New York artists gained notoriety for vivid street tales and a mixing the jazz-influenced style of Rakim with the syncopated flow of Big Daddy Kane. First it was Raekwon and Ghostface Killah, two members of the newly-formed Wu-Tang Clan, which featured nine rappers. With their 1993, debut ‘Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)’ Rae and Ghostface, along with Method Man, established lengthy careers in rap and influenced an entire generation of up-and-coming rappers.

Among those influenced were Jay-Z, a former student of Big Daddy Kane’s, Nas, a friend of A Tribe Called Quest’s frontman Q-Tip, Notorious B.I.G., who was signed to Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs’ Bad Boy label, Mobb Deep, also from Queens natives like Nas, and Busta Rhymes, who was a part of Leaders of the New School and featured on the A Tribe Called Quest party-track “Scenario”.

Immediately following the success of Wu-Tang, was the success of Nas who was seen as the “next great thing from New York”. With Rakim-like poetic delivery, Nas elevated any beat he rapped on, even when they were produced by the best producers of the time including Q-Tip, Heavy D, MC Serch, Pete Rock (“The World is Yours”) and DJ Premier. His debut, ‘Illmatic’, was an instant classic but failed to do well commercially. Mobb Deep’s ‘The Infamous’ album was also designated a classic album, with its hit song “Shook Ones Part II” which is long-considered the mid-90s rap anthem.

Christopher “Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace., started rapping just years earlier, and met Sean Combs, a young executive from Uptown Records (which had success with R&B acts such as Mary J. Blige) was looking for a young talent to start a new label on his own. Combs convinced B.I.G. to quit the drug game just in time to capitalize on his talents and record ‘Ready to Die’, which went on to multi-platinum and “5 Mic” status with hits like “Big Poppa” and “One More Chance”. Many considered B.I.G. the best rapper ever from that point on. Last of this New York group was the energetic Busta Rhymes whose “Woo-Hah! Got You All in Check” rose up the charts in 1996 and launched a still-going career of chart success.

Although some regional groups such as Houston-based Geto Boys, Bay Area rapper E-40 and Miami-based 2 Live Crew gained popularity amongst rap fans, it wasn’t the early-to-mid ‘90s that rap fully began spreading its tentacles beyond the Coasts. In 1994, Chicago’s Common experienced both success and resentment (from Ice Cube) for his single “I Used to Love Her (H.I.P.H.O.P.)” which talks about the history of hip hop and its artistic and creative downfall due to gangsta rap. Also in 1994, Outkast’s debut ‘Southernplayalisticadillacmusik” was dropped and earned recognition from true hip hop fans around the country, although it wasn’t until their follow-up ‘ATLiens’ dropped in ’96 that the group started getting wider national attention. Along with Jermaine Dupri, who produced Kriss Kross and Da Brat, Outkast - backed by Organized Noise and Goodie Mob - helped put Atlanta on the music map.

With hip hop’s arms spreading through the budding success of rappers all around the country, the overall success and growth of the music form still came down to the traditional battle of East Coast vs. West Coast. Unfortunately, these battles materialized themselves into the voices and lyrics of two popular rappers: B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur, who had previously befriended the Brooklyn rapper.

Tupac had already experienced success from his first three studio albums ‘2Pacalypse Now’, ‘Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z’ and ‘Thug Life Volume 1’. Songs like “Brenda’s Got a Baby” and “I Get Around” demonstrated the contradictory themes that would highlight Tupac’s career. Also, Tupac was a budding actor, having starred in captivating roles in the 1992 film ‘Juice’ and the 1994 film ‘Above the Rim’. Tupac, however, still focused on his fast-rising rap career, at least until he was shot five times in 1994. After several legal run-ins, Tupac began serving a prison stint, and from jail his ‘Me Against the World’ album hit #1 on the Billboard chart. Fueled with conspiracy theories about his shooting, both in his head and in the media, and the continued star status of B.I.G. and Puff Daddy, Tupac was released from prison and joined Death Row Records where label owner Suge Knight was already made famous for hanging Vanilla Ice out of a balcony to force a pay-off for his “Ice Ice Baby” success.

With label owners Suge Knight and Puff Daddy taking jabs at each other, their respective rapper friends joined the fray. Tupac’s ‘All Eyez on Me’ and B.I.G.’s ‘Ready to Die’ took shots at each other’s credentials, consummating in an industry-wide East vs. West battle for rap music’s supremacy. The battle was short lived, but it survived long enough to lead to the shooting deaths of both Tupac (Sept. 7, 1996 in Las Vegas) and B.I.G. (March 9, 1997 in L.A.). Hip hop, from that point on officially died according to some critics, while others contend the music form had already been lost and rap music had formally taken over with the murders of two rap legends.

With hip hop music on the decline, highlighted by the breakup of A Tribe Called Quest, and the end of an era with West Coast rap, New York was back on top. Only this time, there were no guns involved in the battle for the throne. Instead, two friends - Jay-Z and DMX - put the music form on their backs and shared the load in the latter part of the ‘90s. Jay-Z’s 1998 “Hard Knock Life” and 1999 “Big Pimpin” were pop chart successes and DMX’s debut album ‘It’s Dark and Hell is Hot’ went on to sell four million copies on the strength of his single “Get at Me Dog”. The two would later co-headline the Hard Knock Life Tour, which was the first major rap tour since the Def Jam heyday in the late ‘80s.

While Jay-Z and DMX brought unique talents to the lyrical platform, it was their beatmakers - lead by Timbaland, Swizz Beats - who followed Dr. Dre and legendary Nas and Notorious B.I.G.-producer DJ Premier by raising the profile of the producer in making a hit album. Perhaps, more than anyone else, Puff Daddy benefited from this new transition since he was credited with having produced albums for dozens of artists even when it was not him, but one of his dozen or so “hit makers” who actually did the work. Puff Daddy’s ‘No Way Out’ album made the most of this producer-friendly environment, along with the death of his best friend, B.I.G.

Jay-Z and DMX were the kings of rap, but they weren’t alone at the top of the charts. New Orleans crashed the coastal party with the success of Juvenile ‘400 Degreez’ and Cash Money group Hot Boyz, which featured a young Lil’ Wayne who has since gone on to a mildly-successful solo career. Master P’s No Limit Records were also part of the onslaught of New Orleans-based hit records. And back in New York, the Latin rap scene exploded with the success of Fat Joe protégé Big Pun’s debut ‘Capital Punishment’.

Not to be forgotten, Dr. Dre returned to the production throne with his third album ‘Chronic 2001’ which featured his renewed collaboration with Snoop Dogg and more work from his most recent chart-topping artists protégé, Emimen. A white rapper from Detroit, Eminem stormed the scene with his debut ‘The Slim Shady LP’ taking jabs at Britney Spears, N*Sync and other pop acts of the day. “My Name Is” quickly rose up the charts of Total Request Live, the latest video show on MTV that helped push rap even further into the mainstream.

Following the continued success of Dr. Dre, several producers continued raising their profiles. The 2000s can be considered the “producer era” in rap music history with Timbaland, Swizz Beats, Pharrell and the Neptunes, Lil' Jon, and Kanye West all dropping solo albums after years of success as producers for popular rappers including Snoop Dogg, Jay-Z, St. Louis-based Nelly and Atlanta-based Ludacris, who both became chart-topping regulars in the decade with their respective 2000 debuts, ‘Country Grammar’ and ‘Southern Hospitality’.

Another development of the early 2000s was the rapper-singer collaboration, which is not new to hip hop (LL Cool J did a song with Boyz II Men in the mid-90s), but greatly expanded in recent years. Ja Rule rose to fame on the strength of his songs with singers Jennifer Lopez, Ashanti and Christina Milian. His fancy for rapper-singer collaborations also drew the ire of fans and other rappers, including the up-and-coming rapper 50 Cent, who was shot nine times and nearly died in 2000. Regardless, rap-sung collaborations have grown to the point of requiring the Grammys create a new award category, and nearly every rap album features a song of this sort. Jay-Z’s relationship with Beyonce is but an example of the growing relationship between rap and R&B music.

With producers having little to no obligation to produce for one particular artist, the 2000s have seen the enhanced role of collaboration and fostering of “camps” of rapper friends. As for the collaboration, this is most notable with production albums by the likes of Atlanta’s Lil’ Jon, Virginia natives the Neptunes led by Pharrell, and Timbaland (also from Virginia) whom have all showcased their production skills on albums featuring all the popular rappers of the last decade. The “camps” concept is evident with the launching of rap’s current stars, 50 Cent, Kanye West, and T.I.

50 Cent, discovered by Run-DMC’s Jam Master Jay, which is a strange circle-of-life type of story when one considers 50’s near-death experience in 2000 mirroring Tupac’s story and Jay’s 2002 death which came just months before 50’s debut album ‘Get Rich or Die Tryin’ went on to sell over 10 million copies in 2003 through Dr. Dre and Eminem’s joint-venture to sign the Queens rapper and create an offshoot label, G-Unit Records. The Game, Young Buck, and Lloyd Banks are other artists whom have experienced success while signed to G-Unit. The Game has since left G-Unit after the multi-platinum success of his 2005 debut ‘The Documentary’ led to a feud between himself and 50; the departure is discussed in “Doctor’s Advocate” on his 2006 follow-up of the same name.

Chicago-based producer Kanye, influenced by the Native Tongues crew and New York producers like DJ Premier, was able to raise his profile by aligning himself with Jay-Z, and hip hop acts such as fellow Chicago native Common, whom he would later help to gain his first major taste of commercial success with ‘Be’ in 2005. Singer-songwriter John Legend of “Ordinary People” Grammy-fame has also joined Common on Kanye’s label, G.O.O.D. Music, while Kanye himself remains on Jay-Z’s Rocafella Records. Recently, Pharrell, Kanye, and fellow Chicagoan Lupe Fiasco, whose 2006 ‘Food & Liquor’ won over critics, if not millions of fans, have joined to form a group that will feature their collaborative efforts.

In closing, the ‘80s saw the introduction of hip hop to the nation, the ‘90s saw the expansion of hip hop’s step-brother rap, and the 2000s have been about the enhanced role of the rapper-executive, regional allegiance (and collaboration) and the importance of the producer. Hip hop and rap are permanently married, but one can only hope they are the type of couple that grows more similar with each passing year. There are plenty of skeptics.

Noteworthy events of the still-unfinished decade include the battle and reconciliation of Jay-Z and Nas, Jay-Z’s ascension to CEO of Def Jam Records, a aforementioned battle between 50 Cent and The Game, the continued success of Atlanta, and other Southern rappers, and the “scratch my back” collaborative environment of rap and R&B these days.

Perhaps intentionally I saved my mention of Atlanta-rapper T.I. for last because his career demonstrates the current trend and trajectory of rap music. He started out on the mixtape circuit rapping tales of drug trade and life on the streets that also made 50 Cent popular in the early part of the decade, then earned himself a label deal only to end up in jail during its peak (‘Trap Musik’) much like Tupac before him.

After his release from jail, T.I. quickly aligned himself with the top producers, rappers, and singers of the day on his platinum albums ‘Urban Legend’ and ‘King’ which featured The Neptunes, Mannie Fresh, Just Blaze, Nelly, and Jamie Foxx. He had a notable battle with Houston rapper Lil’ Flip and has had lyrical run-ins with both Lil’ Wayne and Ludacris. He’s been featured on hit songs with Destiny’s Child (“Soldier”) and Justin Timberlake (“My Love”), won Grammys, started himself a movie career (‘ATL’ and the upcoming Denzel-Crowe flick ‘American Gangster’), and befriended Will Smith and Jay-Z along the way.

Now, you can see T.I. in Chevy commercials with Dale Earnhardt, Jr., his songs are featured on ESPN (“Big Things Poppin”), his friends are having success (Young Dro’s “Shoulder Lean”), and he’s earned himself the “King of the South” title he proudly boast on his records. It’s only proper that his latest album has a track called “Help is Coming” which states “I got the game on lock, it ain’t gonna stop/say hello to the man that could save hip hop”.

Not bad for a guy that grew up in the ghetto, tried to make it 'up' as a drug dealer, ended up serving prison time, and has since become one of the most notable artist today.

Hip hop and rap music, like the yin/yang concept of T.I.’s current chart-topping album T.I. vs. T.I.P., is constantly at odds with itself, but at the end of the day they still need each other.

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

Musically Gifted, Educationally Sound

Having played in the concert and marching band for several years in middle and high school, I fully appreciate the skill and practice that goes into preparing for a recital. When the National Endowment of the Arts are willing to put their stamp of approval on young talents, you should know you're in for a real treat.

Now, having previously discussed the important role of music - albeit in pop culture - I found it quite fitting that at this juncture I would find myself in the company of such gifted young musicians. It should go without saying that I am a big fan of music. Jazz, hip-hop, rock, symphony, you-name-it.

And this brings me to the oft-discussed notion that says learning about music can help a student perform better in school. I haven't read all the research and studies, but I'm in full agreement. Not simply because of the way certain musical scales and notes allow a student to better understand mathematics, or the way interpretations of song and poetry can enable a student to better grasp literature.

Instead, I think learning about music is simply a good way to connect to people. And by connecting to new people, one broadens his or her horizons.

At this particular event, just five blocks down the street from the White House and in the middle of a city filled with political aspirants, it was delighting to be in a room of musicians and the ensuing conversation about the role and impact of music in our lives.

It sure beats talking about politics everyday.

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Connecting Good Causes With Good People

Project links Black professionals, groups looking to diversify leadership ranks

Sara Murray

The Arizona Republic

Jul. 12, 2007 12:00 AM

She became involved in the Black Board of Directors Project last year.

The Phoenix-based organization, which counts more than 700 members, connected her with groups looking to add African-Americans to their leadership ranks.

"I feel like I'm bringing a different set of perspectives, and it's not only because I'm an African-American," said Henry, a director of marketing for Harrah's Entertainment.

While important strides have been made since the group was founded in 1984, leaders say they still must work to increase the number of African-American professionals, particularly within the ranks of local companies and non-profits.

"We want people to be involved in the total fabric of the community . . . not just be involved in the Black community," founder Marvin Perry said.

"Whether you're talking about art and culture, we want to be there. Whether you're talking about law and jurisprudence, we want to be there."

Perry founded the project when he noticed that companies wanted to diversify their boards but didn't know where to find suitable candidates.

"The problem was they all knew the same four or five individuals," he said.

He has helped place members on boards of non-profit organizations, corporations, and municipal, county, state and federal operations.

It can be a challenge. African-Americans make up a mere 3.1 percent of Arizona's population.

In 2000 for example, they comprised 2.3 percent of Arizona's workforce in management, business and financial, according to that year's U.S. census, the most recent data available.

They made up 2.3 percent of health care professionals and 2.6 percent of science, engineering and computer professionals.

Theressa Jackson, a member for about 20 years, was recently appointed chair of the Phoenix Women's Commission.

"When I go and tell folks I'm a member of the Black Board of Directors, I can't say enough for what that has meant for people I've tried to mentor," she said. "It can give you that support you need when you're trying to make upward mobility kind of steps."

More to do

Perry said one of his goals is to see an African-American on the Arizona Board of Regents and the board that heads the Arizona Department of Transportation.Additionally, few Black Board members serve on corporate boards.

While Perry did not have an exact count of members on corporate boards, he said it was minimal.

The Black Board of Directors has been criticized for not putting enough African-Americans on the boards of the largest companies in the Valley.

"Any person of color, if you're going to make a major change in the corporate structure, you need to be where you can affect their policy," said Wilbert Nelson, president of the Arizona state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

"I don't see the companies and corporate structure actually recruiting African-Americans for paid board positions. When it comes to really putting them in a position to impact policy, there's still a way to go."

George Dean, president and CEO of the Greater Phoenix Urban league, said corporate boards are significant because they hold a sense of prestige and influence that is unmatched by public and non-profit boards.

"They're . . . the policy makers for corporations, and corporations drive the economic engine that serves the economy," he said.

The challenge with placing African-Americans on corporate boards is that most board members are former company CEOs, Perry said.

African-Americans are not very prevalent in that pool.

Arizona counted 17,230 people serving as chief executives in 2000, according to census data. Only 105 of those were African-American, about 0.6 percent.

Those affiliated with Black Board aren't shying away from the task.

"To affect change, you have to be on the inside," Jackson said. "We tried it on the outside perspective when we were doing the marches and things in the civil rights era,and that only took us so far."

Jackson said she was a student at Van Buren Elementary School, one of the seven original test schools in Topeka, Kan., following the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling.

"It may be a slower process, but it took us all these years to get where we are, so it's not like we're going to be able to shoot a cannon and change things overnight," she said.

Monday, July 9, 2007

New Album, New Inspiration

Some may wonder how a rap album can inspire me to write, especially when I'm working on a book that sets out to inspire African-American youths to pursue careers outside of the glam and fame they see on TV (and music videos). Let me say this: T.I. is more inspiring to me than the Huxtables.

Now don't get me wrong, T.I. was a drug dealer for many years before he found fame as a rapper and now actor (he starred in last year's ATL). However, what his story - and his predecessor Jay-Z's story - demonstrates is that opportunities are there to be had by historically and socio-economically disadvantaged youths.

Where the Huxtables and their stories were fictional (although perhaps based on happenings in real, affluent African-American households), T.I.'s story is very real. This is not to say that his lyrics aren't controversial nor are they worthy of a Pulitzer, but I don't think I'm the only under-25 African-American male who looks at T.I. and sees progress. And inspiration.

He rose from the streets through crime, but has now turned his focus to (legal) fields that utilize all of his talents. He's a highly-skilled rapper (been called "Jay-Z of the South"), a budding actor (next appears in American Gangster with Denzel Washington and Russell Crowe), a businessman (he is co-CEO of his label, Grand Hustle, and owns a real estate company), philanthropist (has helped rebuild dilapidated homes in his hometown), and pitchman (Chevy ads with NASCAR star Dale Earnhardt, Jr.).

T.I.'s story isn't quite Oprah Winfrey's story, but you can believe there are thousands - if not hundreds of thousands - of young black students across the country who connect more with his adolescent experiences. Just look at his Billboard ranking come Wednesday vs. Oprah's ratings (and who her target audience is) this week.

And this brings me to his new album, T.I. vs. T.I.P. It's his fifth album, and each of his previous albums have brought him more money and fame, but this is his first concept album. The concept behind the album is that "T.I." is the camera-ready, professional side of his personality and "T.I.P." is the street-taught, hustler-inspired side of him.

The inspiration in this is simple: you can be both. Too often, young black children see rappers as "real" and professionals as "sellouts". T.I.'s album is about the inner-struggle between those two. In that, I realize the fine line Louis and I must achieve with this book in order to connect with our target audience, which is young African-American students.

These students, especially those in inner-cities and impoverished areas, know more about T.I.'s experiences than those of the Huxtables. But through it all, we must showcase how people from T.I.'s neighborhood can succeed like people living like Cliff and Claire.

T.I. is still struggling to toe that line, but I am inspired by his attempt.

Friday, July 6, 2007

Michael Eric Dyson's new book on hip-hop

Michael Eric Dyson's new book, Know What I Mean: Reflections on Hip-Hop, hit stores this week. Buy a copy. If his reputation as the "hip-hop intellectual" or subject matter "hip-hop" don't intrigue you enough. How about you read the book's foreword by the best rapper alive: Jay-Z.

INTRO by Jay-Z

Michael Eric Dyson came up in the tough streets of Detroit. He didn’t grow up with silver spoons at the family table. His table didn’t have fine china and his path from then to now wasn’t clear of trouble and strife. He came up through the church and the world of academia in spite of his experience. Dyson confronted the same disadvantages that afflicted the folks in his neighborhood and that held so many brothers and sisters back. But these circumstances opened his mind to learning, and to a sense of justice that has driven him to succeed. Dyson could have been someone’s older brother on my block when I was coming up in the Marcy projects in Bed-Stuy. He could have been the teacher at a Baltimore high school who showed Tupac that there was power in knowledge and your people’s history.

Although he wasn’t there for either of us then, his preaching and his intellectual actions are there today for countless brothers and sisters, regardless of skin color, and regardless of who they pray to at night. He is there telling everyone who was born into a life that seems destitute and destined for failure that there is a way out. He is there reminding us all not to let our situation be an excuse when it can be a resource. Just as important, he is telling all of those countless people whose minds are closed by bigotry or contempt that hip hop is American. Blackness is American. I am American.

At this point it might seem hollow to repeat what has been widely said about Michael Eric Dyson: this gifted man is the “hip hop intellectual,” a world-class scholar, and the most brilliant interpreter of hip hop culture we have. But plain and simple that is what he is. He has shown those doubters and critics that hip hop is a vital arts movement created by young working-class men and women of color. Yes, our rhymes can contain violence and hatred. Yes, our songs can detail the drug business and our choruses can bounce with lustful intent. However, those things did not spring from inferior imaginations or deficient morals; these things came from our lives. They came from America.

The folks from the suburbs and the private schools so concerned with putting warning labels on my records missed the point. They never stopped to worry about the realities in this country that spread poverty and racism and gun violence and hatred of women and drug use and unemployment. People can act like rappers spread these things, but that is not true. Our lives are not rotten or worthless just because that’s what people say about the real estate that we were raised on. In fact, our lives may be even more worthy of study because we succeeded despite the promises of failure seeping out from behind the peeling paint on the walls of every apartment in every project.

Dyson came up from the bottom and told those on top what was up. He turned a light on our situation in this country and then he threw down a rope to lift us out. He started out translating between “us” and “them” and now he’s helping put together a world where there is only “us.” How many folk out there can talk about pimping in terms laid out by Hegel? Or use Kant to explain the way that prison fashion moved from the cellblock to the city block? Dyson drops the names of philosophers and scholars as easily as he does the names of artists on the latest mixtape moving dance floors in the clubs. Michael Eric Dyson has taken modern urban life seriously and brought the tools of so-called legitimate society to bear on a place that too many dismissed as unworthy of attention. Just by mentioning these cats in the same breath he levels a playing field that has always been tilted. He tore down the last “whites only” sign in the university and let all of us rush in to hear what the ancient teachers and scientists had to say.

Dyson stands up for poor folks and for street culture when other African Americans treat us with the same disdain that white society used to have for all of us. He continues to show us what the past can teach us about our present. It’s one thing for young people to see rappers making appearances on TRL or to see their records fly up the charts. But it is another thing for a young boy from the hood to go into the library at his school and check out a book on why his culture matters. Quite literally, Dyson has written that book. Money comes and goes, but respect can last for generations. Neither the IRS nor the changing taste of the public can take away what Michael Eric Dyson has given to hip hop: respect and a better way to understand ourselves.

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

We need more from you, Mike

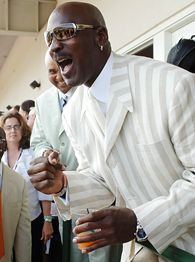

I was walking down a busy Manhattan street the other day when I came across a large window display that caused me to do a double take.

It featured a dark-skinned brother promoting a new shoe for which a portion of its proceeds went to Project Red.

I paused because I thought the guy was Michael Jordan.

It wasn't.

His Airness has always held a precarious place in my heart. My admiration for his passionate play is constantly at battle with my frustration for his apparent lack of passion for anything that doesn't benefit him.

When I think of the large cultural space he occupies -- even in retirement -- and the fact "Republicans buy sneakers too" remains his most memorable contribution to the political landscape, I am truly baffled that he can rest peacefully at night. I don't care if he's a Republican, Democrat or Libertarian. But while his iconic Nike labelmate, Lance Armstrong, has become synonymous with yellow wristbands and the cancer fight, MJ, who is far more influential, continues to steadfastly sidestep using his image for social change, even as it relates to issues of the global black community.

Silence about AIDS in Africa.

Silence during the Hurricane Katrina aftermath.

Silence in the fight against, well, just about anything.

Except slumping shoe sales.

Now some of you are thinking, "Haven't I read this criticism of Jordan before?" to which I say, "Yes, you probably have." Others are wondering, "Why does he have to do anything?" Let me answer that one too: He doesn't.

Nevertheless I bring this challenge up today because, one, the NBA is welcoming a new collection of young men with the potential to do great things, and two, I feel the black community needs a powerful voice such as Michael Jordan's now more than ever.

The U.S. Justice Department estimated six years ago that one in six black men were either in prison or ex-cons. Today the trend is approaching one in three. There are more black men in prison than there are in college, and those who are not in prison are having a significantly more difficult time finding employment than their white and Latino counterparts.

Growing up, people wanted to be like Mike, especially young black men. We shaved our heads, stuck our tongues out on the court and supported his apparel unconditionally. That's why three years into retirement he's still able to sell $250 shoes. Now that he's done playing, how about using those large hands to reach back as opposed to climbing up? How about some comparable reciprocity? I'm not suggesting coming out against the war in Iraq. But something as Q-rating safe as aggressively addressing the woes of inner-city education could go a long way to help the people who never hesitated to be there for him.

Before going any further, I would be remiss if I didn't acknowledge that Jordan has done, and continues to do, a great deal of philanthropic work. I know that his mother, Deloris, is a tireless worker who has taken up such causes as helping to build a Boys and Girls Club in Chicago and providing aid to villages in Africa. I know these things because I looked it up. Of course finding the Jumpman logo took a lot less effort.

And that's why my love for Jordan is at odds with my disappointment. Hell, as far as I know, he might have been instrumental in getting Chuck Taylors involved with Project Red behind closed doors, seeing how Nike owns Converse. But the black community persevered through years of oppression by relying on the sacrifices of the nameless and the talents and resources of our mythical figures. We may not be facing the same civil rights obstacles that prompted Muhammad Ali and Harry Belafonte to speak out, but the community is in no less need of a visible rallying voice.

One with enough clout and respect that he could call up a Pacman Jones or Tank Johnson and tell him to stop acting like a fool. And maybe he has. I don't know. But what I do know is that 20 years ago we were not afraid to look after each other's children, share food, or, if need be, check each other for the sake of the community. But now that the fire hoses have been turned off, we've grown content to look after self. And that's what MJ appears to be doing -- looking after self. I don't know if he shares my political views, but black-on-black crime isn't just action. Sometimes it's inaction, and to paraphrase Dr. King, one day we're going to have to repent for it.

And I'm just as guilty as anyone else. Sometimes I feel so overwhelmed by the ills that plague our society in general, and my community specifically, I become paralyzed by the enormity of it all -- opting to send a faceless check to some organization rather than roll my sleeves up to fight a war that I'm not sure can be won.

Maybe that's why MJ, the man who hates to lose, is unwilling to get his name more involved. He knows "Jordan" can sell shoes. He's not sure "Jordan" can save the world. Or maybe Jordan just doesn't care as much as I, or perhaps many of you, had hoped. A disappointing possibility, for sure. It would be as if Superman spent his time pushing T-shirts with an "S" on them instead of saving lives.

When I spoke with a number of black athletes about philanthropy and the black community, they were reluctant to call MJ out. And really I wasn't looking for them to do so. The fact that no one could tell me anything about him that didn't have to do with Nike or basketball said it all.

"Jordan's still the most influential athlete in the world in my opinion, so yeah, whatever he does is going to draw a lot of attention," says New York Jets linebacker Jonathan Vilma. "I'm not disappointed he's not more visible in terms of causes and things like that because everybody has to decide what's best for them. I just try to focus on doing everything I feel I can do to help those less fortunate."

Josh Childress of the Atlanta Hawks agreed.

"True, he doesn't use his celebrity as much as he could but maybe he just wants to stay under the radar, who knows?" says Childress, who routinely works with underprivileged children. "Growing up, people did strive to be like Jordan, and yeah, if he did something really big to fight prostate cancer or something like that, a lot of guys would support him just because it's Mike."

Warrick Dunn, whose Home for the Holidays program is one of the most inspirational projects spearheaded by any athlete, says he finds being in a position to use his name to give back is an honor.

"Michael is the greatest athlete of our generation," says Dunn, the Atlanta Falcons running back. "I'm sure he's done a lot, and he could probably do more with his fame. But at the same time he's just one man and you have to ask, 'How much can one man do?' I mean, every professional athlete can do something to make the world better."

Like Tiki Barber, who one day strolled into the office of Newark Mayor Cory Booker and asked what he could do to help. It's that kind of gesture Booker says he focuses on, more than what others are not doing.

"I've always tried to live my life by the basic principle my parents taught me from the Bible," Booker says. "To he much is given, much is required.

"I cannot discount the inspirational power of just seeing Michael Jordan or Tiger Woods achieve athletic greatness and the positive effect it has on the black community. But while it's true we live in a free democracy, we have to understand this democracy was born out of incredible self-sacrifice. It wasn't even a generation ago that you saw the extreme sacrifices made by people whose names we don't even know. Now we're in a state of crisis, and black athletes can help change that. The call is out there, but I can't be frustrated by those who don't answer the call."

But I can.

In 2005, we cheered Kanye West for saying George Bush didn't care about black people after he bungled Katrina relief efforts. Yet less than two years later we're wondering whether New Orleans is going to have enough police to contain all the violence and ghettofabulousness for next year's NBA All-Star Game. With disconnects like that, who needs the KKK? We're eliminating ourselves from the equation, and it seems as if our elite are too busy to care. I now understand what Marvin Gaye meant when he said "It makes me wanna holler and throw up both my hands."

I wonder if Jordan is ready to holler yet.

And if so, why can't we hear him?

LZ Granderson is a senior writer for ESPN The Magazine and host of the ESPN360 talk show "Game Night." He can be reached at l_granderson@yahoo.com.

Monday, July 2, 2007

Education through Refutation, Introducing Louis

"The points you made are similar to those of (Bill) Cosby. While I don't disagree that African-American parents of kids who use this kind of language lie at the heart of this problem. It is often easy to point fingers at the cause of our problems, but this doesn't give rise to solutions.

Okay, so it's true that some kids have parents who are less than desirable (to put it lightly). These kids, through no fault of their own grow up in a less than desirable environment and can only function in ways and exhibit behaviors that they have experienced. If those of us who have made it out, or were fortunate to have never been in such an environment, simply disengage, these young people may never have an opportunity to realize that there is a better way to express themselves. If all they experience is deficient parenting, deficient schooling, and are perceived as deficient by the larger society, there is little chance for climbing out of a deficient and dysfunctional environment.

Let’s point the fingers in all directions, not just at parents. Let’s point at a society that will send its least prepared and least successful teachers to inner city schools upon which they spend the least money. Let’s point fingers at an entertainment industry that promotes and glorifies those who spew the negative language into African-American communities, while those who's rap lyrics promote positive messages are virtually ignored. Let's point fingers at a society that will immediately cheer on a successful African-American athlete while minimizing the accomplishments of African-American scholars, businessmen, attorneys, engineers, teachers, physicians, ...

Let's point the finger at us, middle-class African Americans who look upon poor African Americans with disdain when we ourselves are only a generation or two (or a paycheck or two) away from poverty. Let's point the finger at a society that operates as if racism no longer exists and points to African -merican athletes as evidence of equal access to the American dream. Let's point a finger at a society that tells young African-American kids that everything about them, their color, their language, their attire, their hairstyle, their music, their home environment, their values, their perspective on life,... it's all wrong, its all negative; and that they must assimilate (act white) to be acceptable.

Let's stop pointing fingers only at impotent parents and start reaching a hand to their children, even if they don't want your hand. Let's give these young people a chance to see that there is a better way to live, that there is hope if their dreams are given direction, that there are opportunities if they prepare themselves. I know this to be true because I am here.

Thank God you were raised in a positive environment. Others of us have not been so fortunate. Nothing personal, just my two cents."

-Louis Harrison, Ph.D.

Three points and two pennies

Ebony magazine's current issue has a pretty bold cover (above). I haven't read the article completely, but I do know one of its lines read: "This whole thing started with three words. “Nappy-Headed Hos.'"

Now, my question is this? Did we really wait until 2007 and a guy named Don Imus to have a candid discussion about race, vernacular and "the culture of disrespect"? Why did we wait so long? Was it because it wasn't front-page news until Imus said it? Was it because Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton were on primetime news doing interviews? Was it because it was about the women's basketball team of Rutgers University? Was it because rappers like 50 Cent are famous for songs that include similar phrases?

I can't really answer those questions. All I can do is offer my two cents.

Personally, I think there are three problems with the topic that we're only just now beginning to be honest and frank about within the African-American community.

The first problem is parenting. Just as African-American parents should encourage their children to perform in the classroom (and their respective athletie or artistic endeavor), parents must encourage their children to surround themselves with good people. I have never used the n-word or the derogatory terms for females commonly stated in songs by rappers when addressing any individual, man or woman. The reason? Because I've never been arund anyone who would tolerate those types of words coming out of my mouth.

That said, parents must try to educate their children on the importance of being around good like-minded people. They must also practice what they preach. Just as you wouldn't want to put your child in a room filled with smoke, you shouldn't put your child in a room of foul-mouthed adults.

The second problem is about pop culture and the overly-emphasized role it has in the African-American community in particular. It is not uncommon for a young black student to recite the lines of rapper 50 Cent or know the best scoring move of Kobe Bryant, yet not know enough to make a passing grade in the classroom. There is nothing wrong with enjoying rap music or basketball. There is something wrong with not enjoying school enough to make it to the next grade.

Again, parents play an instrumental role in making sure children prioritize their lives. Educators, and administrators, must also understand the role of pop culture on these young students and find new, innovative ways to inspire students to seek the same wealth and professional success as the people they see on television, only through the education.

Lastly, the problem is with blame. Too often, we seek to blame before we seek to understand. What does Stephen Covey's 7 Habits of Highly Effective People tell us? "Seek first to understand, then to be understood." Exactly. In order to make the Don Imus' of the world understand, completely, why they can and should never be allowed to say the derogatory things they sometimes say (or want to say), we must - as an African-American community - understand why we have allowed these words to be said within our own community. Our music. Our streets. Our schoolrooms. Our homes.

Before we can blame, we must listen. By listening, I believe we can really move the needle forward to a day when children can listen to 50 Cent's lyrics without using that negative, derogatory language themselves.

But that's just my 50, I mean two, cent.